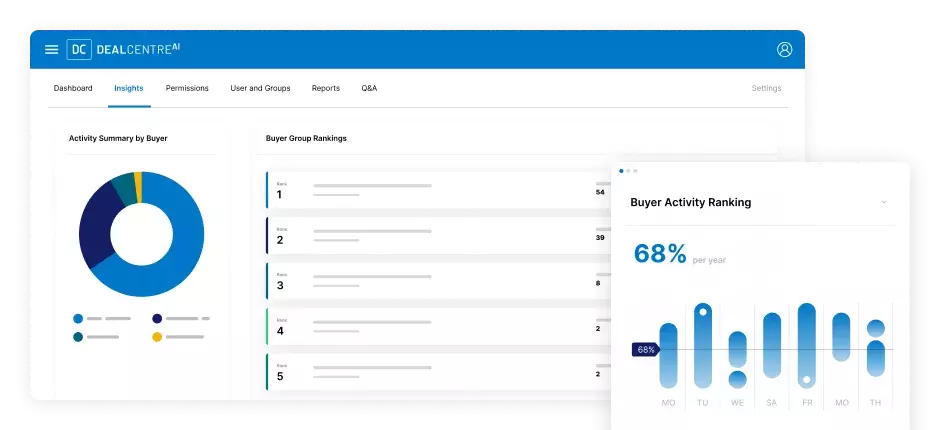

在此完成 交易。

深具智慧。

憑藉業界領先的安全及效率為您的策略性交易提供支援。包括併購,銀團貸款到募資,引進投資者,基金報告等。

深受世界500強及頂尖造市商信賴

Raytheon

$ 898 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進 United Technologies 以 898 億美金收購 Raytheon。

Dow

$ 573 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促成進Dow Holdings Inc. 以 573 億美金進行股東分拆。

Anaplan

$ 103 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進 Thoma Bravo 以 103 億美金收購 Anaplan。

Whole Foods

$ 136 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進Amazon 以 136 億美金收購 Whole Foods。

Fortress

$ 33 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進SoftBank 以 33 億美金收購 Fortress Investment Group。

TSG Consumer

$ 60 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進TSG底下TSG9的基金募資。此傳統併購型基金專注於消費產業

Neuberger Berman

$ 25 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進 Neuberger 的 NB Credit Opportunities Fund II的募資輪。

Riverside

$ 18.7 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進 Riverside 的 Micro-Cap Fund VI 募資輪。

Hayfin

$ 66.1 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進 Hayfin 的 Direct Lending Fund IV 募資輪。

Summit Partners

$ 15.2 億

SS&C Intralinks 成功促進 Summit Partner 的 Europe Growth Equity Fund IV 募資輪。

全球 值得信賴 的

金融科技供應商。

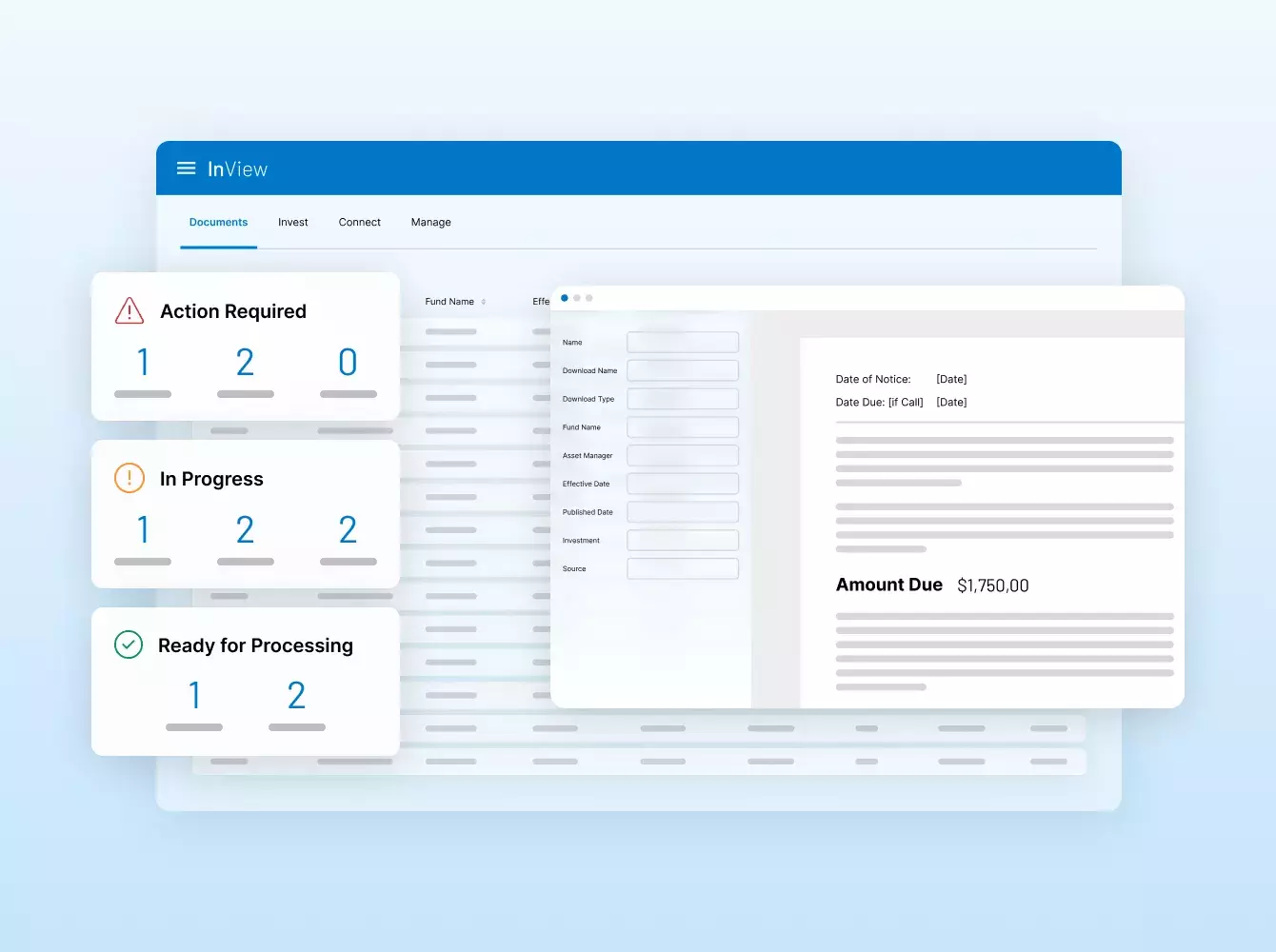

Intralinks 在 20 多年前率先成立虛擬資料室,並持續創新至今。我們的解決方案推動全球最大的資本市場交易,並為 GP 提供世界級的 LP 體驗。

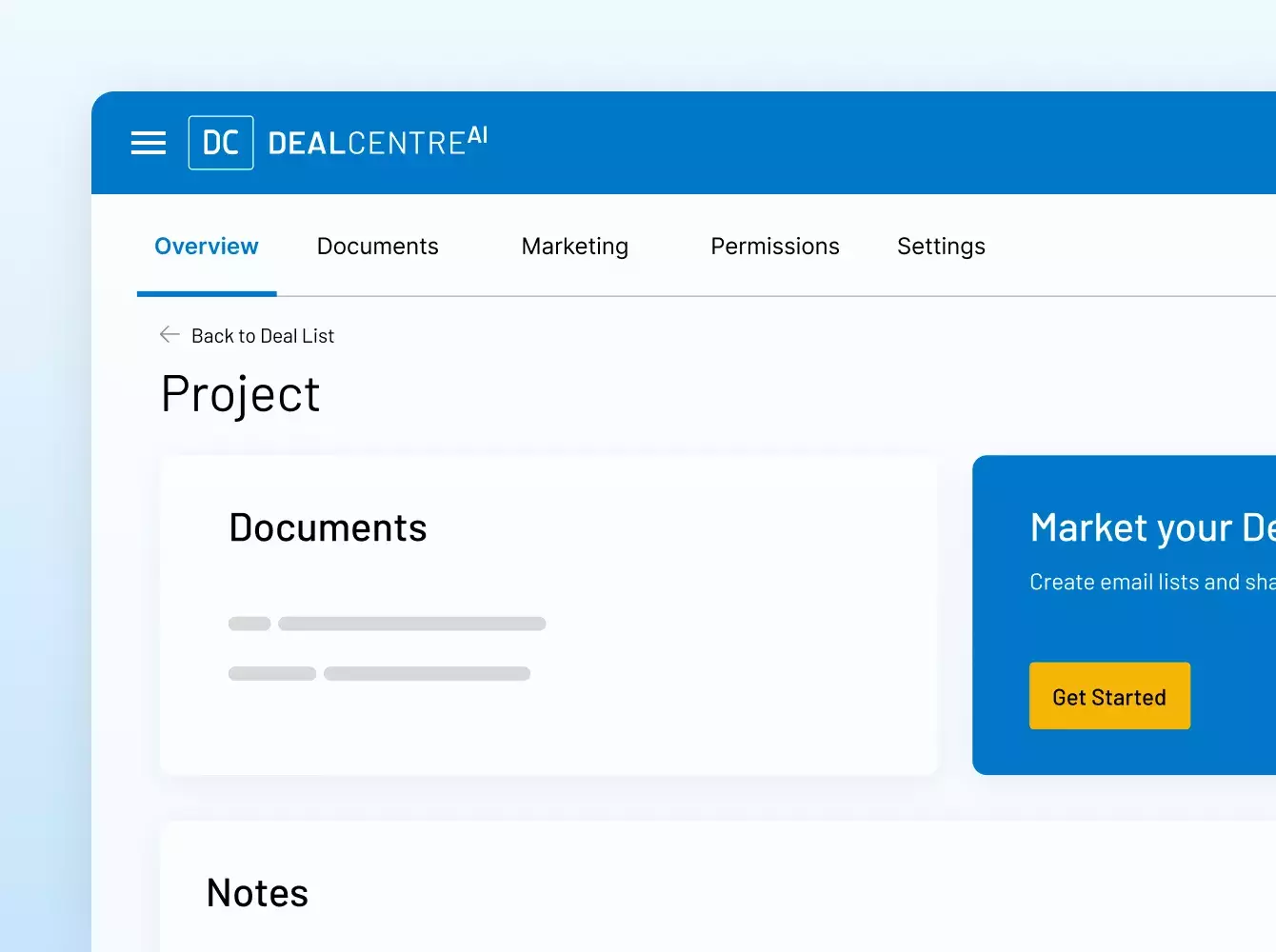

預約DEMO#1 併購交易解決方案

涉及超過 35 兆美金的金融交易

#1 GP-LP 社群

包含515,000名用戶,來自 來自超過10萬家企業

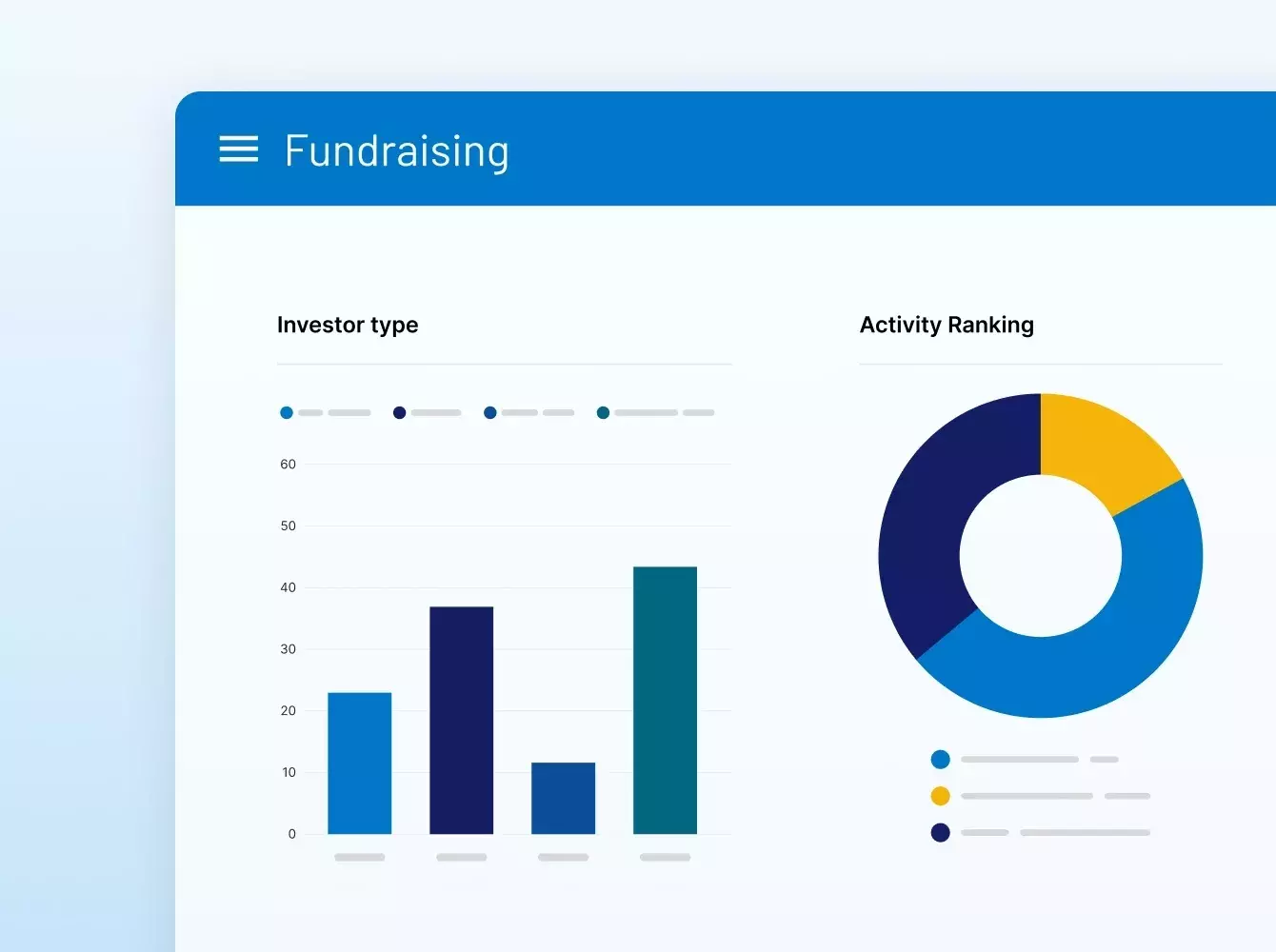

#1 募資平台

全球超過一半的資金透過本平台籌集

超過 2 億美金

在過去五年對研發的投資

ISO 27701

第一家獲得最高資料隱私標準認證的 虛擬資料室供應商

6 秒

接通我們屢獲殊榮的支援團隊 平均所需的時間

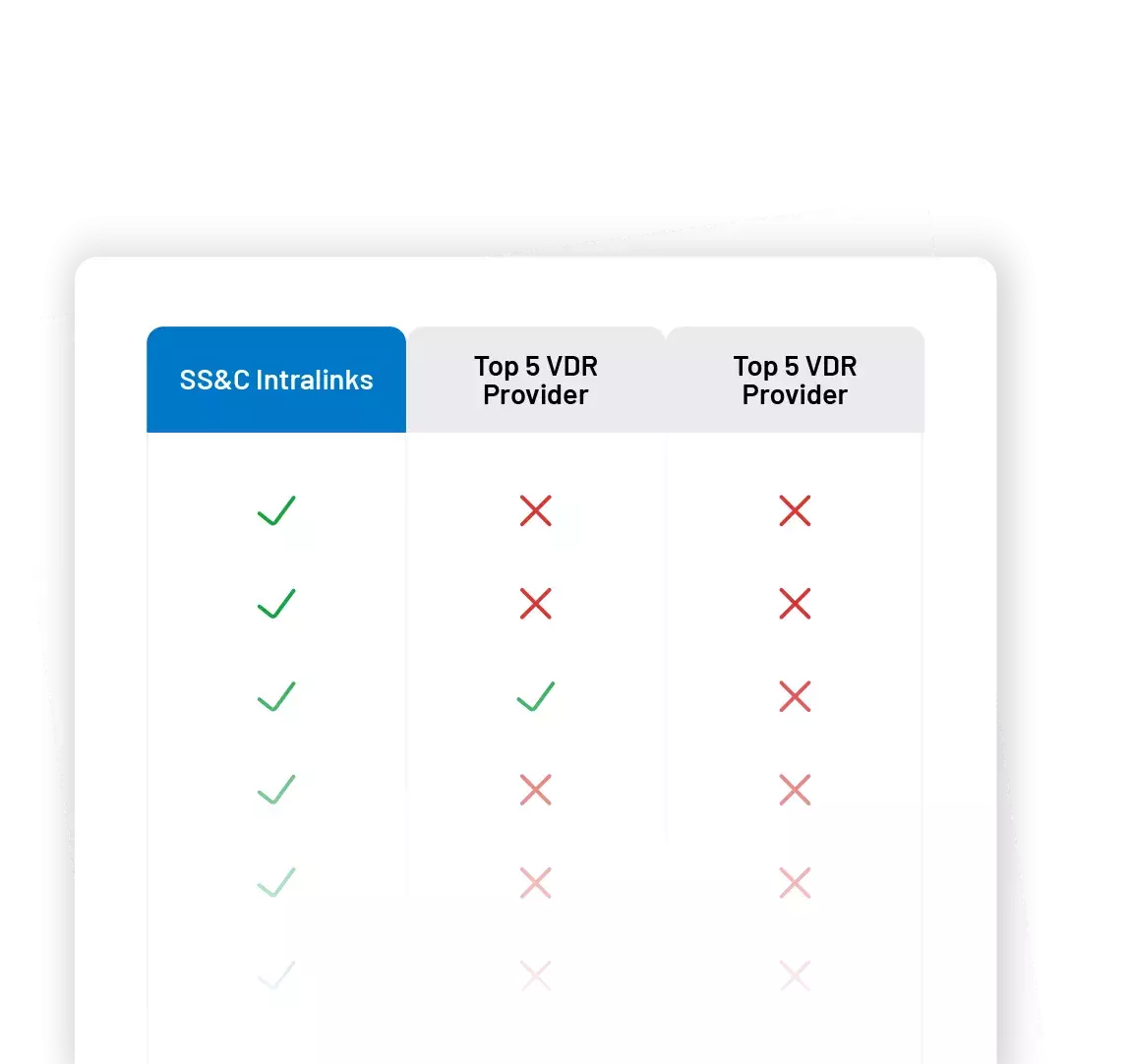

Need to advise your client

on how to choose a VDR?

Advisors often need to present their clients with a comparison of VDR alternatives. To save you time, we built a template that includes a feature comparison between top VDR providers.

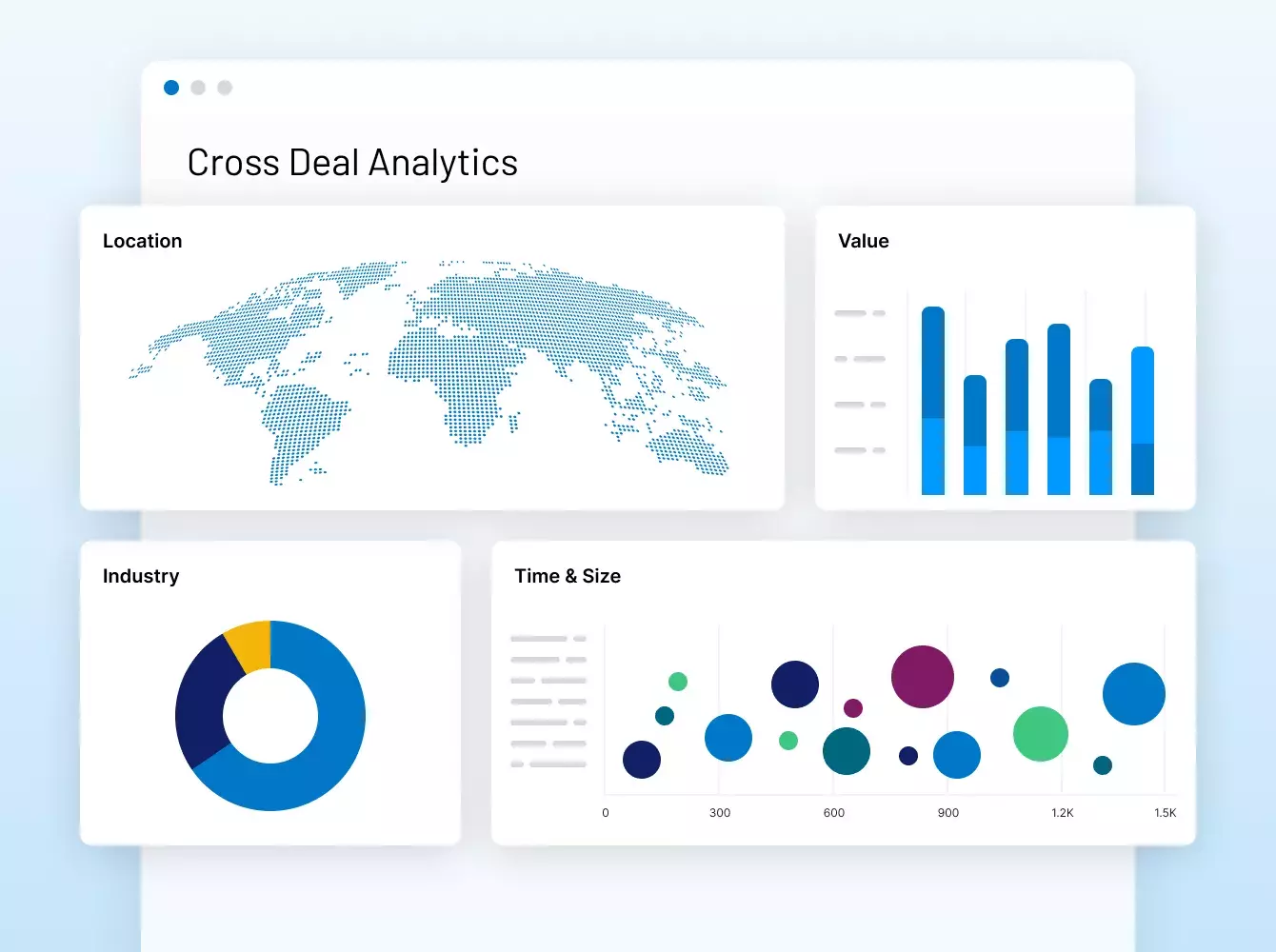

為什麼需要把資料存放在一個安全的位置

金融交易涉及大量文件,其中許多包含機密和敏感資訊。選擇可信賴及透過認證的供應商非常重要。在 Intralinks,我們的使命是透過安全的生態系統來保護您的專案及相關資料。確保您、您的客戶及您的合作夥伴的安全。

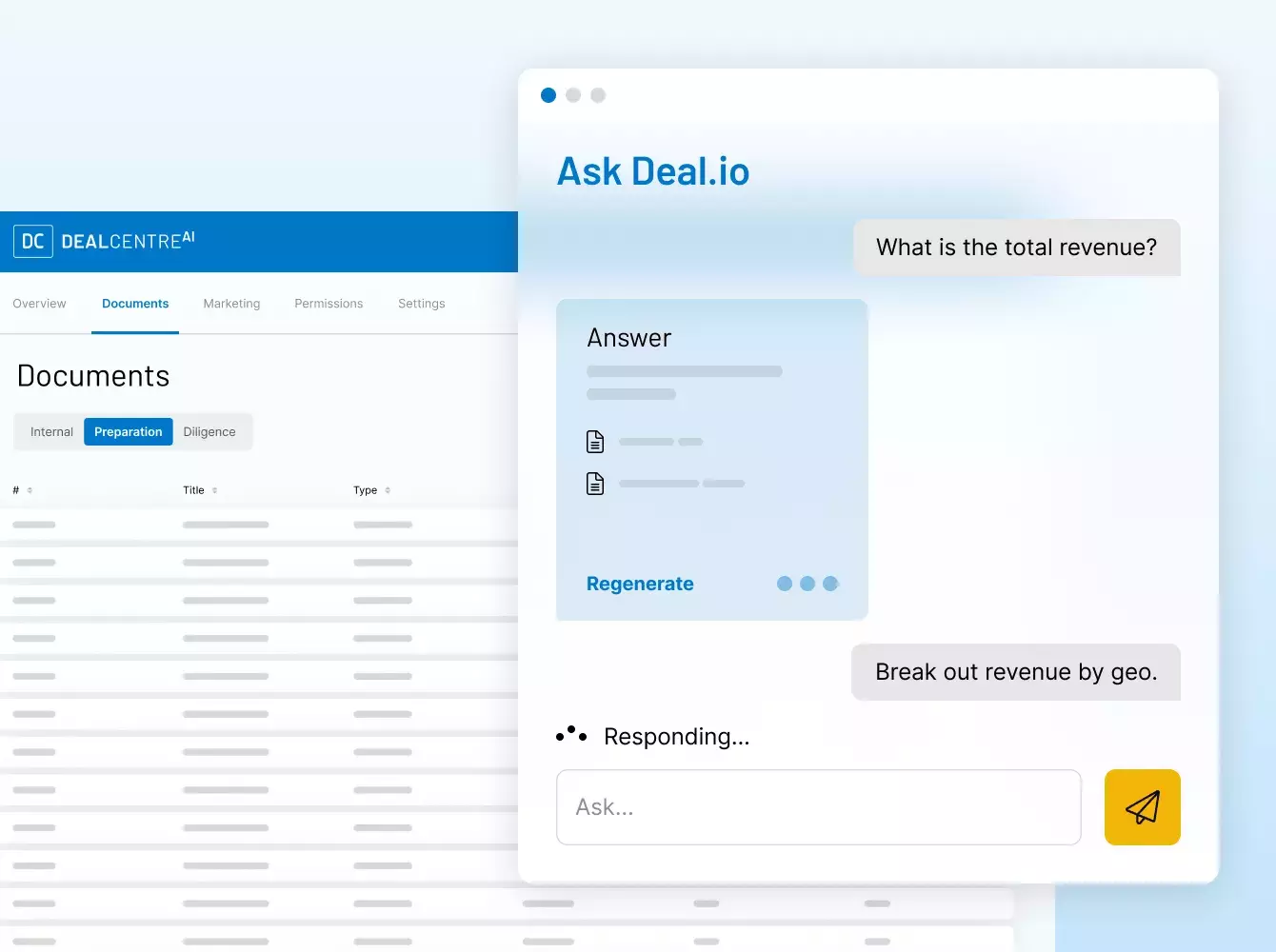

你們還提供哪些額外的服務?

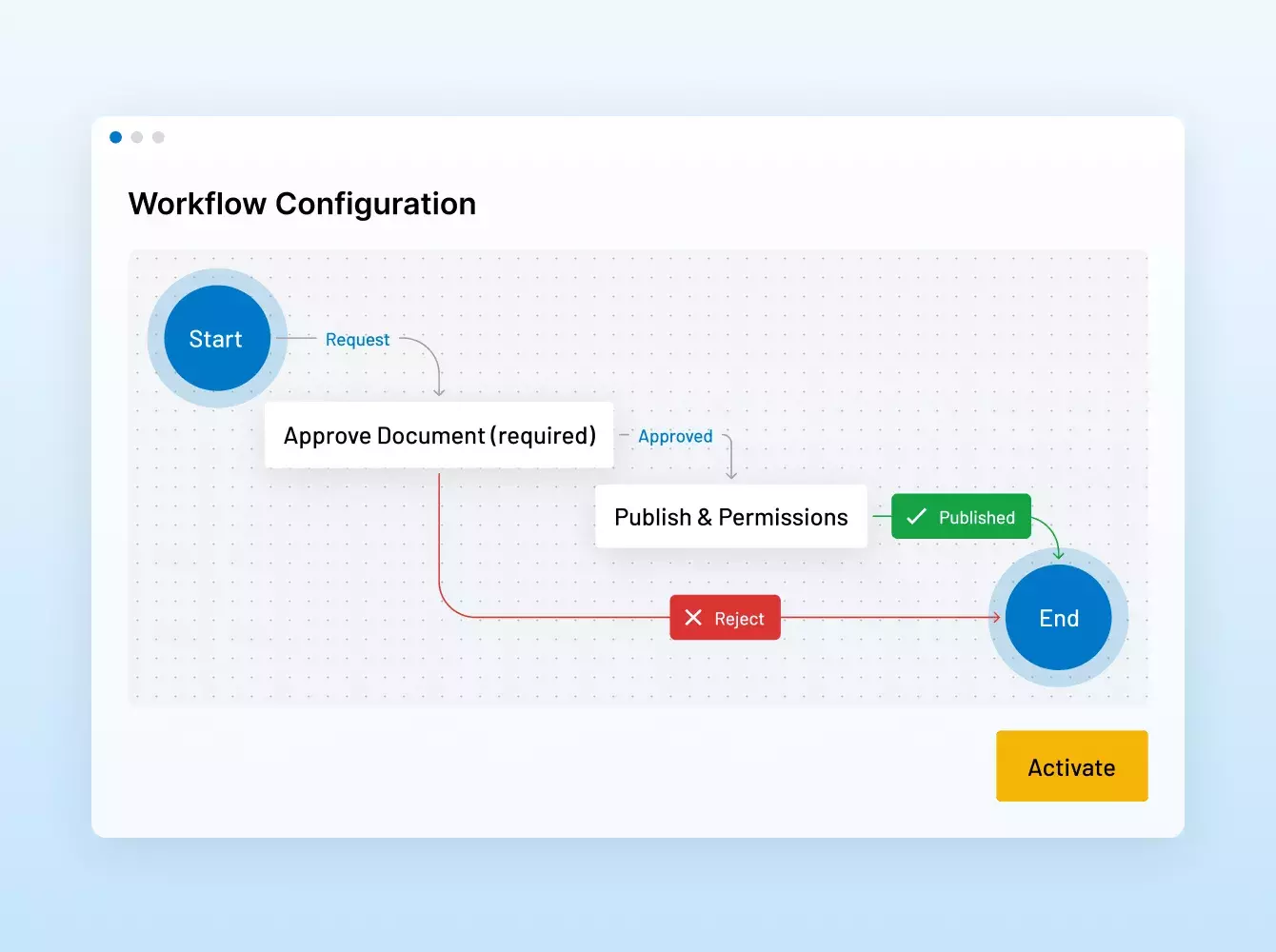

無論我們的客戶是需要設置虛擬資料室上的協助, 額外的協助完成繁瑣的事宜如:塗黑文件,NDA,或者是客製化方案去解決自動化或複雜的整合方案。Intralinks的團隊隨時準備提供協助。我們的服務結合了開創性技術、行業專業知識和數十年的經驗,以滿足專案在各個階段的需求。

為何選擇你們,而非其他供應商?

作為虛擬資料室的創始者,Intralinks 不斷創新,使用專業的解決方案和銀行級別安全防護來保護客戶的資料和聲譽。我們得到金融技術企業龍頭SS&C的支持,他們的年收入超過 60 億美金雖然我們競爭對手削減研發及服務的開支。但是我們仍持續投資,過去五年投入超過 2 億美金,為客戶帶來世界一流的體驗。

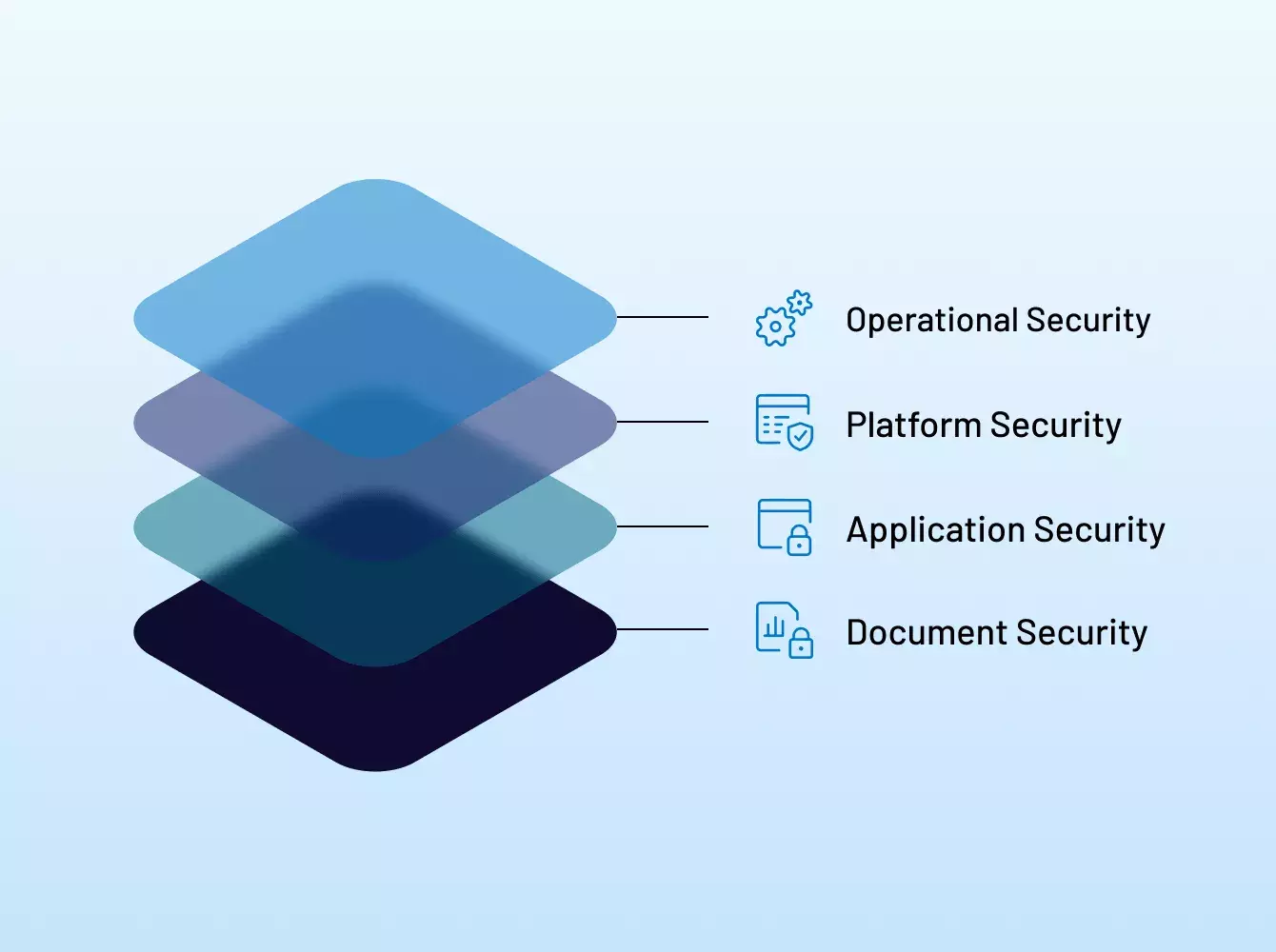

其他檔案共享解決方案真的有同樣的安全性嗎?

不。雖然其他供應商聲稱其產品安全,但他們往往使用模糊且具誤導性的措辭來掩飾其真實的安全資質。我們的全面安全策略包括業界領先的認證和合規實踐,覆蓋 Intralinks 的人員、流程、政策和支撐基礎設施。

Latest INsights

Industry-leading thought leadership, insights, events and resources.