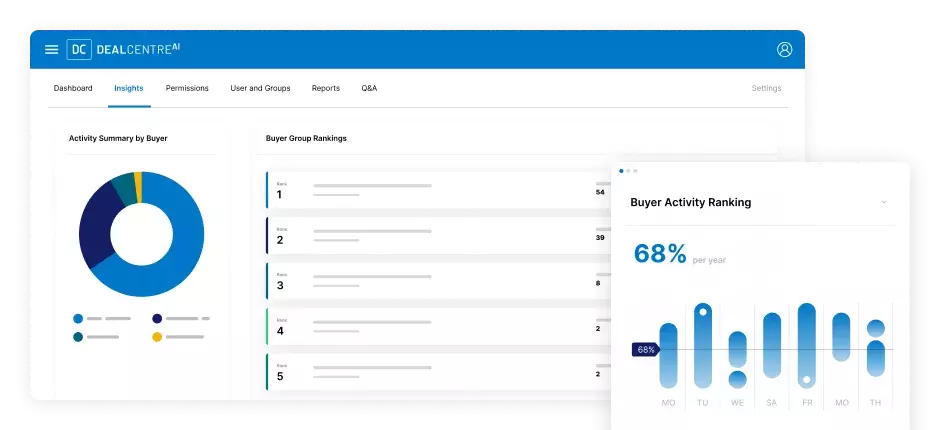

La plateforme où se concrétisent les deals les levées de fonds les introductions en bourse les syndications et les financements

.

En toute intelligence.

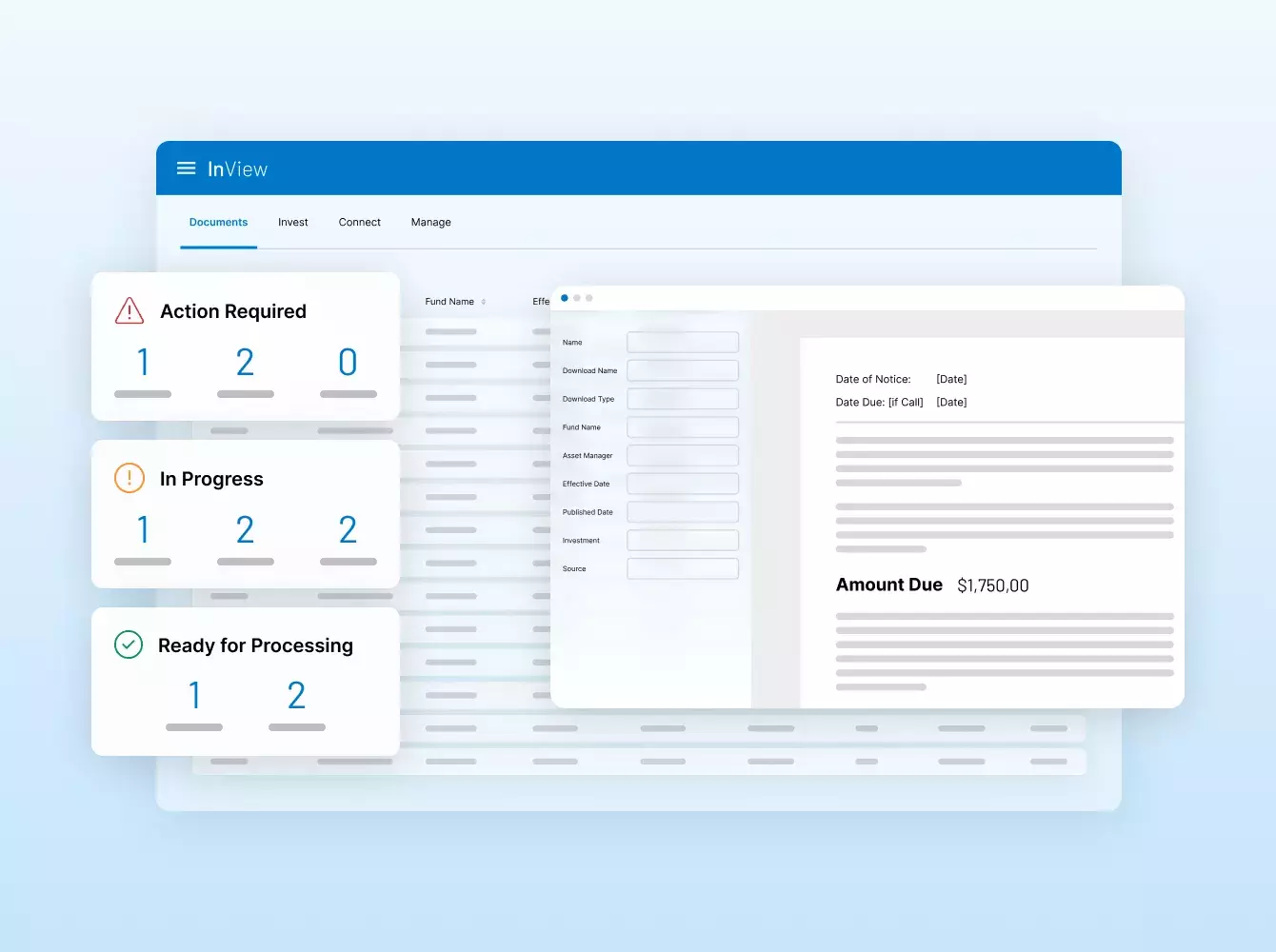

Avec une sécurité et une efficacité inégalées, nous accélérons toutes vos opérations clés : M&A, prêts syndiqués, levées de fonds, intégration d'investisseurs, reporting financier… et bien plus encore.

Les entreprises du Fortune 500 et les plus grands acteurs des marchés financiers nous font confiance:

Raytheon

$ 89,8 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité l'acquisition de Raytheon par United Technologies pour un montant de 89,8 milliards de dollars.

Dow

$ 57,3 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité la scission de 57,3 milliards de dollars de Dow Holdings Inc. au profit des actionnaires.

Anaplan

$ 10,3 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité l'acquisition d'Anaplan par Thoma Bravo pour un montant de 10,3 milliards de dollars.

Whole Foods

$ 13,6 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité l'acquisition de Whole Foods par Amazon pour un montant de 13,6 milliards de dollars.

Fortress

$ 3,3 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité l'acquisition de Fortress Investment Group par SoftBank pour un montant de 3,3 milliards de dollars.

TSG Consumer

$ 6 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité la levée de fonds pour TSG9, le fonds de rachat de TSG axé sur le secteur grand public.

Neuberger Berman

$ 2,5 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité la levée de fonds pour le fonds NB Credit Opportunities Fund II de Neuberger.

Riverside

$ 1,87 milliard

SS&C Intralinks a facilité la levée de fonds pour le fonds Micro-Cap Fund VI de Riverside.

Hayfin

$ 6,61 milliards

SS&C Intralinks a facilité la levée de fonds pour le fonds Direct Lending Fund IV de Hayfin.

Summit Partners

$ 1,52 milliard

SS&C Intralinks a facilité la levée de fonds pour le fonds Europe Growth Equity Fund IV de Summit Partner.

Summit Partners

$ 1,52 milliard

SS&C Intralinks a facilité la levée de fonds pour le fonds Europe Growth Equity Fund IV de Summit Partner.

Le fournisseur de technologies financières de référence

dans le monde entier.

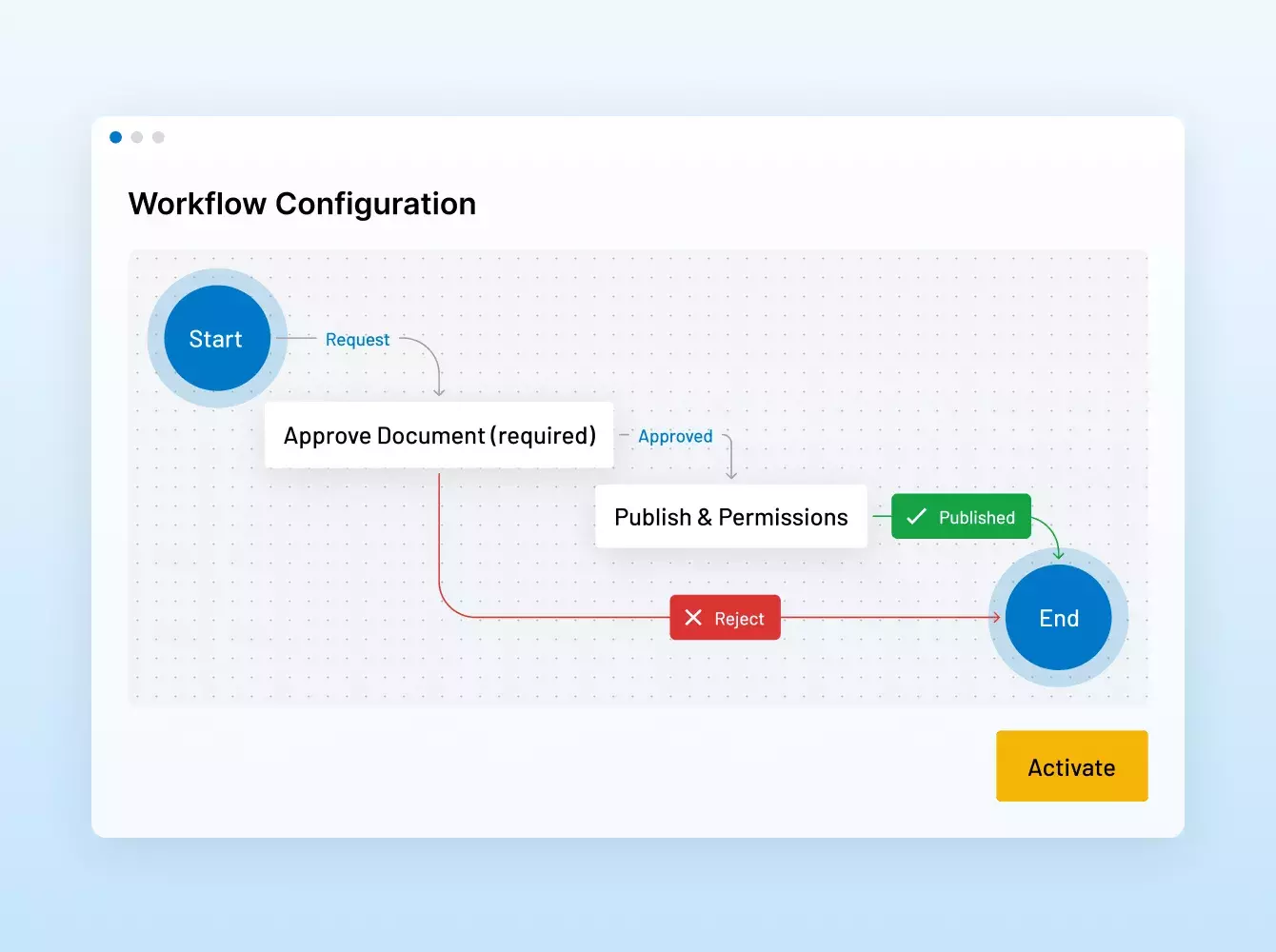

Intralinks a imaginé les VDR il y a plus de 20 ans déjà et n'a cessé d'innover depuis. Nos solutions sont utilisées pour mener à bien les deals des plus grands marchés de capitaux au monde et permettent aux gestionnaires de fonds de proposer des expériences de premier ordre à leurs investisseurs.

NOUS CONTACTERN°1 en M&A

Des solutions représentant plus de 35 000 milliards de deals financiers

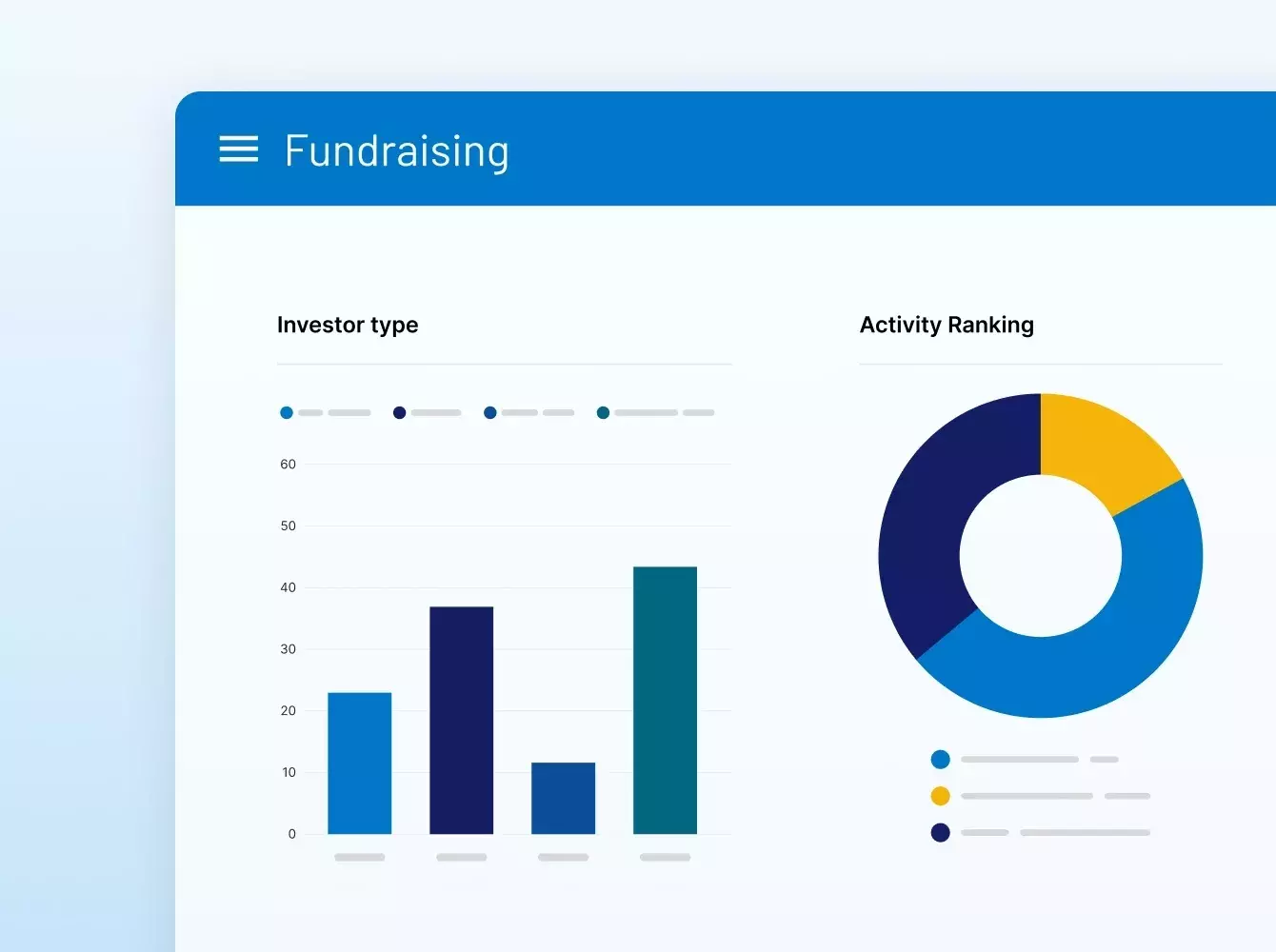

n°1 des gestionnaires et investisseurs

Une communauté de 515 000 personnes et de plus de 100 000 entreprises

N°1

Plateforme de levée de fonds

Plus de la moitié des sommes levées dans le monde

Plus de 200 millions de dollars

En investissement dans la R&D sur les cinq dernières années

ISO 27701

Premier fournisseur de VDR à décrocher la certification la plus stricte en matière de confidentialité des données

Leader

IDC MarketScape : Évaluation 2024 des fournisseurs de logiciels de fusion et acquisition

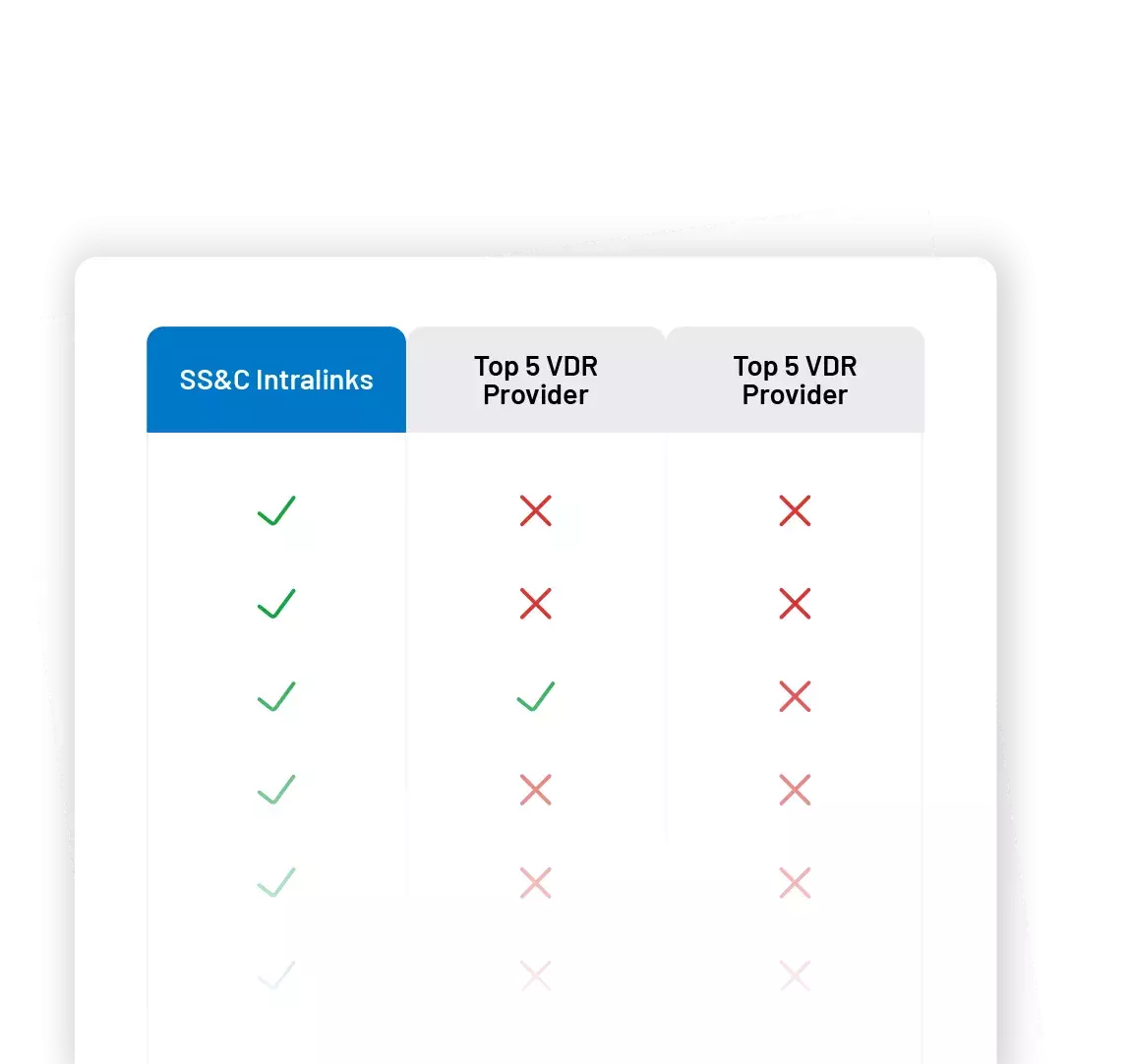

Vous devez guider votre client

dans le choix d'une VDR ?

Les conseillers doivent souvent présenter à leurs clients plusieurs solutions de VDR. Pour vous faire gagner du temps, nous avons préparé un modèle comparant les fonctionnalités des principaux fournisseurs.

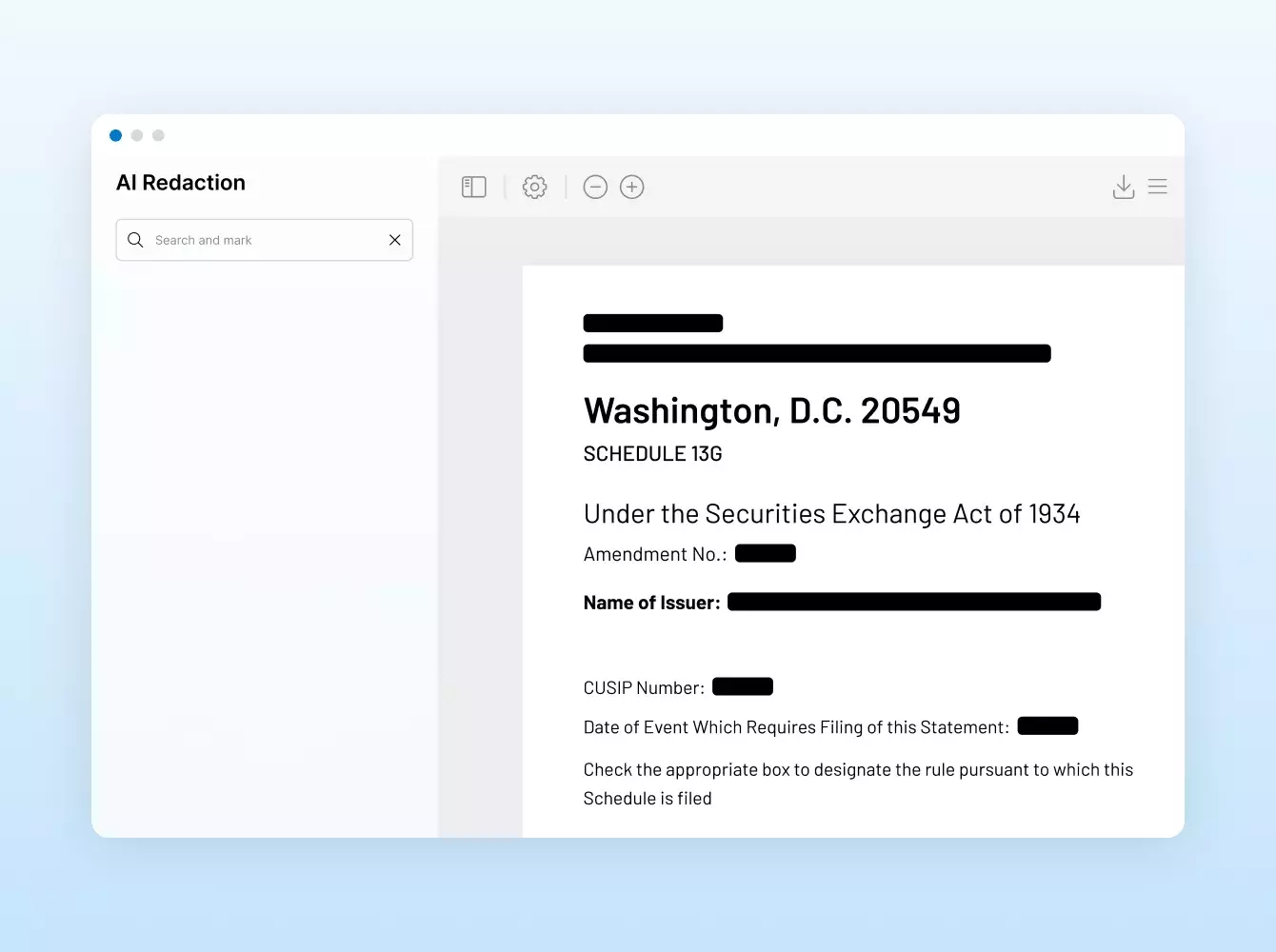

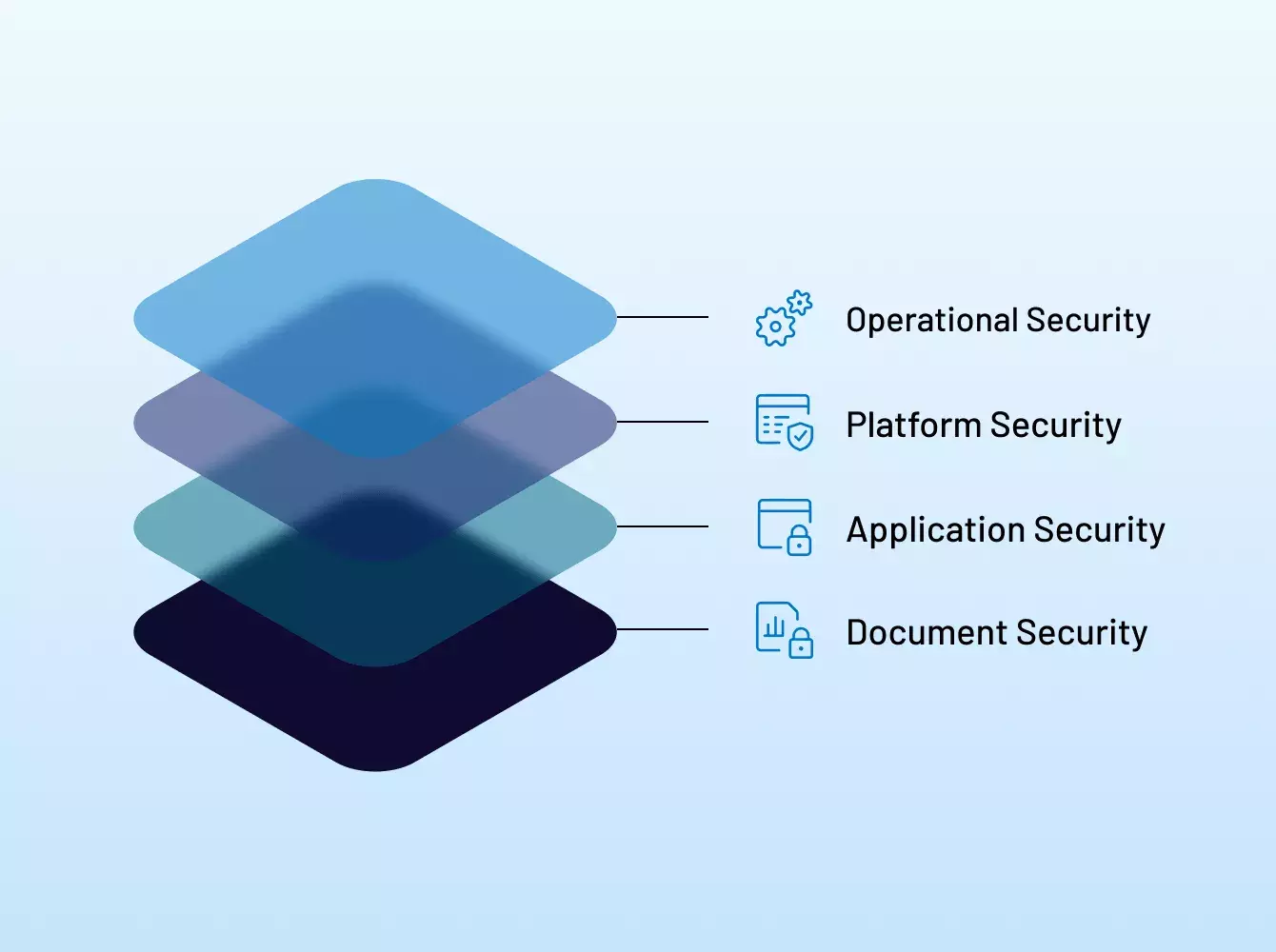

Pourquoi dois-je utiliser un système sécurisé pour mes données ?

Les deals financiers génèrent de nombreux documents, dont beaucoup sont confidentiels et contiennent des informations sensibles. Par conséquent, il est essentiel de choisir un fournisseur fiable et expérimenté. Chez Intralinks, nous veillons à protéger vos deals et données avec un écosystème pensé pour votre sécurité, celle de vos clients et celle de vos partenaires.

Quels autres services proposez-vous ?

Que nos clients aient besoin d'une assistance technique pour la mise en place d'une VDR, de ressources de soutien dans le cadre de tâches difficiles comme la rédaction de documents ou la création d'accords de non-divulgation, ou encore d'une solution entièrement personnalisée combinant automatisation et intégrations complexes, les équipes des services Intralinks sont à votre disposition. Nos services combinent technologies de pointe, expertise sectorielle et des dizaines d'années d'expérience pour répondre à tous vos besoins, quel que soit le stade de votre deal ou de votre projet.

Que proposez-vous de plus que vos concurrents ?

Intralinks est le pionnier des virtual data rooms (VDR) et innove en permanence en proposant à ses clients des solutions adaptées à leurs besoins et offrant une sécurité conforme aux normes du secteur bancaire pour protéger leurs données et réputation. Nous bénéficions du soutien de SS&C, une fintech générant plus de 6 milliards de dollars de revenus. Alors que nos concurrents réduisent leurs investissements dans la R&D et les services, nous avons alloué plus de 200 millions de dollars en cinq ans à ces postes pour proposer une expérience de haut vol à nos clients.

Les autres solutions de partage de fichiers ne sont-elles pas aussi sécurisées que la vôtre ?

Non. Cet argument est mis en avant par nos concurrents, mais beaucoup se montrent délibérément vagues, emploient des arguments trompeurs et ne révèlent pas leur niveau réel de sécurité. Nous adoptons une approche complète de la sécurité, avec des certifications reconnues ainsi que de bonnes pratiques en matière de conformité couvrant tous les aspects du fonctionnement d'Intralinks, à savoir nos collaborateurs, processus, politiques et infrastructure.

Allez de l'avant.

- Meilleure sécurité du secteur

- Présence internationale et fiabilité exemplaire

- Solutions polyvalentes et ergonomiques

- Assistance de pointe